ELECTORAL CHOICES: THE TASK BEFORE THE JUDICIARY

JOSEPH OTTEH, Legal Advocate and Convener of Access to Justice, argues that to end the legacy of impunity in the conduct of elections, Nigeria’s Judiciary and jurisprudence must shift towards principled guardianship of people’s voting rights and sanctity of the electoral process

Introduction

Beginning with the transitional elections of 1999, Nigeria’s efforts to run a system of electoral democracy began in fits and starts; election after election would often represent a worse version of the preceding one. Most post-transition elections have been marred by widespread killings and violence, bare-faced and large-scale rigging, ballot-box snatchings, voting and collation frauds, result declaration frauds and thefts, voter suppression, and so on. Now, ensuring that voting outcomes are rigged sufficiently to return electoral “victories” have became part and parcel of the preparatory layout and landscape of electoral competitions in Nigeria.

Those who steal electoral mandates are emboldened by three major factors: first, rewards and dividends of such thefts are mouthwateringly huge, and so are worth all the grievous efforts expended in procuring them. Second, a successful theft of votes gives strategic legal advantage to its beneficiary. “Law” welcomes and judicially protects such thefts, at least until a certain burden has been discharged. Our laws posit that once an election result is entered in the official record – rigged or not – they are presumed to be correct, even if they are contrived. At this point, “law” is not neutral; it takes sides with those declared to be winners by the electoral body. The Supreme Court has reiterated that: ‘’There is in law a rebuttable presumption that the result of any election declared by the returning officer is correct and authentic.” – Omoboriowo v. Ajasin. Therefore, it is much better, from a legal and tactical point of view, to rig elections, because then, a strategic advantage is gained over other competitors because the “law” gives that evidential advantage.

Third, “impunity”. There are no credible civil or criminal consequences for undertaking these grand “vote larcenies” irrespective of the bloodletting or violence undertaken during voting exercises to distort the results of ballots cast during the at the elections.

This piece considers how Nigerian courts, by applying a pedantic, legalistic approach to the resolution of electoral complaints, are aiding the continuous subversion of the electoral process, betraying the voices of voting majorities and undermining representative democracy. We also explore how courts can better rise to the challenge of protecting the integrity of electoral choices made by voters in the face of treacherous efforts to pervert the electoral process.

Complaints About Election Malpractices Must Be Regarded as “Public Interest Litigations” and Resolved Using Parallel Principles of Adjudication

Complaints about electoral malpractices – rigging, violence, fraud, voter suppression, interference with ballots, and corruption – raise issues that extend well beyond the personal rights, interests or claims of individual complainants or their impact on the electoral fortunes of a candidate or political party, and, while aggrieved complainants are entitled to a fair remedy for any wrongs suffered arising from election malpractices, their grievances implicate wider public interests in the maintenance of representative democracy, the integrity of the electoral process, and the sustenance of constitutional democracy. If aggrieved litigants do not challenge the malpractices arising from the conduct of electoral contests, members of the public have, as individuals, no standing to do so, at least, as current law suggests. This is why a case must be made for courts to regard electoral litigations as a specie of “public interest litigation”, where the petitioners represent a stakeholder demographic whose collective interests in the sustenance of constitutional democracy are endangered or violated.

In Madundo v Mweshemi v. A-G Mwanza, the Tanzanian High Court stated that: “An election petition is a more serious matter and has wider implications than an ordinary civil suit. What is involved is not merely the right of the petitioner to a fair election, but the right of the voters to non-interference with their already cast votes…” In Sarah Mwangudza Kai v. Mustafa Idd & 2 Others the court said: “It must be understood that election petitions are unique in many ways… they can be classified as actions sui generis. This is because they are not actions in which an individual asserts a private civil right as in a civil claim. Petitions are basically instituted for the benefit of all voters in the affected electoral area and generally in the public interest”

In Obih v. Mbakwe, Kalgo JSC made the point that “an election petition is not to be treated under peculiar provisions of the relevant electoral law and is not particularly related to the ordinary rights and obligations of the parties concerned” a point the Supreme Court also reiterated in Buhari v. Yusuf and in a number of other cases.

If courts accept – as have been asserted – that election litigations are sui generis, how have they applied this principle in practice, in resolving election petitions? Unfortunately, it appears that courts have applied the sui generis notion to harden the tasks of challenging and upturning results or returns declared by the electoral body. Purporting to apply the sui generis principle, courts have both insisted that petitioners comply strictly with technicalities of law and procedures in litigating election petitions, as well as meet a very high standard of proof, in order to show that elections were marred by substantial irregularities, enough to affect the outcomes announced by the electoral body. Petitioners have found that mountain too high to climb many a time.

Let’s examine the first proposition, the insistence for strict compliance with technical formalities. Courts have, more or less characterized election petitions as proceedings that require technical perfection. And so, any defect in form or procedure was enough to defeat such petitions (ref. Samamro v. Anka). In David Umaru & Or v. Babangida Aliyu & Ors. (CA/A/EP/317/2007 (CON)) [2009] the Nigerian Court of Appeal said:

It is because of its uniqueness or sui generis nature that any slightest default in complying with a procedural step which otherwise could either be cured or waived in ordinary civil proceedings could result in fatal consequences to the petition. It is not therefore the function of the court to sympathize with a party in the interpretation of a statute merely because the language of the statute is harsh or will cause hardship. That is the function of the legislature”

The second leg of the sui generis invocation, seen both in Nigeria and some other parts of the African Continent, involves the standard of proof required in election petition cases necessary to invalidate election results. Judiciaries have wrestled with the question whether a higher standard of proof – such as the one applicable to criminal trials, i.e. proof beyond reasonable doubt should be applicable to election petitions (ref. Ugandan case of Besigye v Museveni) or the civil standard of “balance of probabilities” generally applicable to civil cases. Other courts have indeed, argued for an intermediate level of the burden of proof (ref. Kenyan case of Odinga and Anor v Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission and Ors and the Ugandan case of Mbabazi v Museveni [2016] UGSC 4), lying somewhere between the criminal and the civil standards of proof. There is also the “alternating” application of both civil and criminal standards, according to the nature of the complaints embodied in an election petition. (Ref, Zimbabwean case of Chamisa v Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa & Others CCZ 21/2019). In the Besigye v Museveni case, the Uganda Supreme Court held that a high standard of proof is required in election petitions given critical importance of the subject matter to the “welfare of the generality of the people of the country and their democratic governance.”

It seems quite counter-intuitive, and counter-productive we submit, to draw, from the notion that election petitions are a sui generis genre of proceeding, any requirement that challenging election outcomes, even where obviously fraudulent or contrived, should be more difficult to achieve, or that petitioners must jump through hoops raised to industrial levels in order to do so. We think, respectfully, that the implications drawn by courts in this direction are unfounded, wrong and misconceive the overarching goals of electoral justice. Courts which have applied the sui generis principle this way get it backwards, and have inverted the flow of the logic.

Purpose of Electoral Adjudication Must Animate Philosophy of Electoral Jurisprudence

The core purpose of adjudicating electoral petitions is, (eligibility questions apart), to enable a court establish who was validly elected into a political office by voters. In order to do this, a number of indicators are applied, such as; was the election conducted in a credible, transparent manner? Did voters freely, fairly and effectively exercise their franchise? What electoral choices did voters make? The role of the court is to give effect to those choices. If it must do so, it seems inexorable that electoral courts must apply the sui generis principle in a way that makes it easier, not harder, to achieve the overriding purpose of a judicial review, i.e. to ensure that voter choices remain the authentic markers and sources of power, not fictitious or fabricated data.

The “standard of proof” bar must, therefore, be recalibrated and lowered, so that petitioners can, without having to “climb Mount Everest” or carry the whole of its weight, make a case enabling an electoral court to feel called upon to upturn the results of a flawed election, irrespective of whether petitioners have brought in every atom and molecule of evidence from the electoral field. If there is credible evidence suggesting that the conduct of elections did not meet reasonable standards of transparency, or was fraught with malpractices showing the commission of fraud or violence, disenfranchisement or corruption, an electoral court ought to consider it its constitutional duty, in the safeguard of a country’s democracy and the rule of law, to invalidate the elections, in whole or part.

If the courts treat election petitions as “public interest litigations”, which, in many ways they are, then their adjudication out to proceed on analogous principles – those of simplicity of procedure, expanded access to court, creative provision of appropriate remedies, etc. etc. The Kenyan Supreme Court alluded to this when it said in Odinga & another v Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission & 2 others; [2017] KESC 42 (KLR): “This means that electoral disputes involve not only the parties to the Petition but also the electorate in the electoral area concerned. It is therefore obvious that they are matters of great public importance and the public interest in their resolution cannot be overemphasized”.

This is the way election petitions ought to proceed, we submit, so that courts can look more to the essence rather than to the form of the complaints; to “doing justice” to the substance of the causes presented before them, rather than to the manner they are garbed or the level of technical perfection they achieve.

That “justice” is not simply for the benefit of the particular petitioners before an electoral court, but even more for the sake of citizens, whose ballots embody and represent their will, election and agency, all of which have come into question. Sachs J, of the South African Constitutional Court once remarked that: “The right to vote is symbolic of our citizenship” August v Electoral Commission (cited in Richter v The Minister for Home Affairs and Others) [2009] ZACC 3. It is also about maintaining the authority of the Constitution in a constitutional democracy. Prof. Nwabueze (2008) made the point that election rigging ‘is a subversion of the Constitution and of the democratic form of government instituted by the Constitution”.

In matters of electoral justice, courts, we submit, must no longer drape their eyes with blindfolds of legalism, because this tends to miscarry the object of electoral adjudication. In its editorial of 27th April 2023, the Punch Newspaper lamented: “For too long, justice and frustration of the people’s will have been sacrificed on the altar of legal technicalities”. That is a valid point.

In a piece published by IDEA titled: “Inside the courts and challenging election outcomes” prominent election observation activist Samson Itodo has observed that “The complex and technical nature of election petitions is largely responsible for the failure of election tribunals and courts to address the grievances of litigants despite efforts at resolving such election disputes”. Justice Niki Tobi, of blessed memory, alluded to this point in Abubakar v Yar’Adua when he said: “If courts of law are bound to do substantial justice in ordinary civil matters, how much less [sic, read “more”] in an election petition.”

The Substantial Non-Compliance Question

Sec. 135(1) of the Electoral Act restrains courts from invalidating elections that were conducted in “substantial compliance” with the principles of the Act where the non-compliance did not affect substantially the result of the election. Courts have interpreted this provision literally, to require that a complaint about non-compliance with the principles of the Electoral Act is of itself inconsequential unless it be shown that the non-compliance affected the results of the election (Buhari v Obasanjo; Buhari v. INEC And 4 Ors.). However, it is reasonably clear that a literal interpretation of the section without balancing that interpretation with the broader objectives of the Electoral Act and important constitutional values, will be strongly inimical to achieving the core objectives of the Electoral Act and the Constitution.

For one, a literal interpretation will likely lead to the situation where the electoral process is “perverted” with impunity. Where courts uphold deeply flawed elections on the grounds that the irregularities and illegalities associated with their conduct did not substantially affect their outcome, perpetrators of these malpractices will feel emboldened to continue in that treacherous trade, leading to the escalation and replication of the culture (electoral) impunity. Courts would, in that case, be legitimizing the continued subversion of the electoral process if they uphold the results wrought by elections of that stripe. A Kenyan Appeal Court said it will amount to courts encouraging “vandalism”, in response to an argument that alleged irregularities in an election should not lead to a nullification because they did not affect the election results;

Again to use the section to cover the disappearance of ballot boxes, irrespective of the number of ballot papers in the missing boxes, would simply amount to encouraging vandalism in the electoral process. (Magara v Nyamweya & Others, Civil Appeal No.8 of 2010) Emphasis added.

It is our position that the current way Sec. 135(1), is interpreted by Nigerian courts is at clear odds with the goal of ensuring free, fair, transparent and credible elections, as well as securing the accountability of election management bodies. Nigeria’s courts must reframe how that section is interpreted in order to make its application more consistent with the spirit of the Electoral Act, and the compelling need to confront – with a view to ending – the legacy of electoral frauds historically associated with conducting elections in Nigeria, and to uphold the principles underlying our democratic Constitution as well as our rights as citizens and voters.

Reframing how that interpretation occurs does not necessarily rule out the invocation of a literal construction; it is still possible, we submit, in applying a literal construction to the section, to “win” justice for the cause of credible elections.

To begin with, we observe that the two conjunctive conditions for invalidating an election under that section are, put in a more direct or positive form: 1) “non-compliance with the provisions of this Act” and 2) that the non-compliance affected substantially the results of the election. On the surface, the impression is given that the non-compliance must significantly impact the announced results to the extent of depriving the declared winner of a majority vote win. On closer inquiry however, we see that this is not the only way to interpret the section, if it is even a legitimate way to do so at all. There is no objective need for the declared winner to lose the majority vote advantage, or, for that matter, for the petitioner to show that s/he won the majority vote, to justify a court’s nullification of the election on the ground that non-compliance with the Act substantially affected the results of the election.

This can be achieved in two ways: first, if the irregularities result in a significant or substantial diminution of the declared winner’s votes, the results of the elections can be said to have been “substantially affected” even if it still leaves the declared winner with a majority of the votes cast. In other words, to “substantially affect” the results does not literally equate to “displace” or “overturn” the result. It means simply “affect”! It is not a situation requiring a zero-sum equation.

A second approach still based on a literal interpretation, is to regard the irregularities as capable of substantially affecting the results if the non-compliance or irregularities has a potential effect to do so, even if the actual effect is not adequately quantifiable or remains unknown. In other words, there is an implied assumption that the non-compliance has an unknown effect on the outlook of the overall results. Also in this scenario, there is no need to prove that the petitioner’s scores would out-number those of the declared winner but for the non-compliance or irregularities.

Having noted these, we must, in summing up, say that a literal construction of electoral enactments which implicate fundamental rights of citizens, (in fact “sovereign” rights as the Odinga court puts it), represents an inadequate and very limited interpretivist framework for realizing the ends of electoral justice. A court must always embed the interpretation of a statutory instrument within the strategic vision, values and philosophy of the overall constitutional pact. Realizing that the right to vote arises from the Constitution, and is a subject of several multilateral treaties and instruments, courts must always give effect to the reinforcing values which underpin those rights.

A proper framework for interpreting Sec. 135(1) of the Electoral Act must, therefore, first take place within the context of all embracing standards – particularly the constitutional standards – governing the right of voters to freely and fairly elect their leaders without interference. Second, it will also regard and denominate the election “process” just as important as the “outcome”. If the process is flawed, the outcome will naturally reflect the “fruit of the poisoned tree” and no restrictions must stand in the way of ensuring the accountability of the process or its impact on the rights of citizens to vote.

In this regard, we can draw inspiration from the approach of other courts in the Continent, Not that long ago, the interpretation of a provision quite similar to Sec. 135(1) of Nigeria’s Electoral Act arose in Kenya, and the Kenyan Supreme Court in Odinga & another v Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission & 2 others was called upon to uphold the results of the 2017 presidential elections in spite of several irregularities in the way the country’s presidential election results were recorded, collated and presented, on the basis that: “if the quantitative discrepancies are so negligible (in this case, allegedly slightly over 20,000 votes), they should not affect the election”. The Kenyan Supreme Court responded quite formidably to the argument, saying:

“… this inquiry about the effect of electoral irregularities and other malpractices, becomes only necessary where an election court has concluded that the non-compliance with the law relating to that election, did not offend the principles laid down in the Constitution or in that law.”

And then went on to say:

“Where do all these inexplicable irregularities, that go to the very heart of electoral integrity, leave this election? It is true that where the quantitative difference in numbers is negligible, the Court, as we were urged, should not disturb an election. But what if the numbers are themselves a product, not of the expression of the free and sovereign will of the people, but of the many unanswered questions with which we are faced? In such a critical process as the election of the President, isn‘t quality just as important as quantity? In the face of all these troubling questions, would this Court, even in the absence of a finding of violations of the Constitution and the law, have confidence to lend legitimacy to this election?” (emphasis added).

The court then ruled:

”It is our finding that the illegalities and irregularities committed by the 1st respondent were of such a substantial nature that no Court properly applying its mind to the evidence and the law as well as the administrative arrangements put in place by IEBC can, in good conscience, declare that they do not matter, and that the will of the people was expressed nonetheless.” –

What the court was saying, in effect, is that the electoral process is just as important as its outcome, and that a judicial body, applying a sovereign Constitution, whose values must be read into electoral laws, should not legitimize flawed elections irrespective of the statistically limited quantitative effects of the flaws/irregularities on the overall results.

Conclusion

The 2023 elections in Nigeria have been cast in the mould of many previous elections, with some saying it’s the worst in Nigeria’s history. The scathing reports by observers of the last elections in Nigeria attest to this, saying the elections were marred with widespread violence, rigging and falsification of results, abduction of election officials, killings, and the lack of transparency among other flaws. INEC’s conduct of the 2023 elections show that Nigeria is still on its backfoot, and unless something breaks this cycle, no barrel will be too deep to plumb going forward, which will bring more shame to the collective dignity of its people.

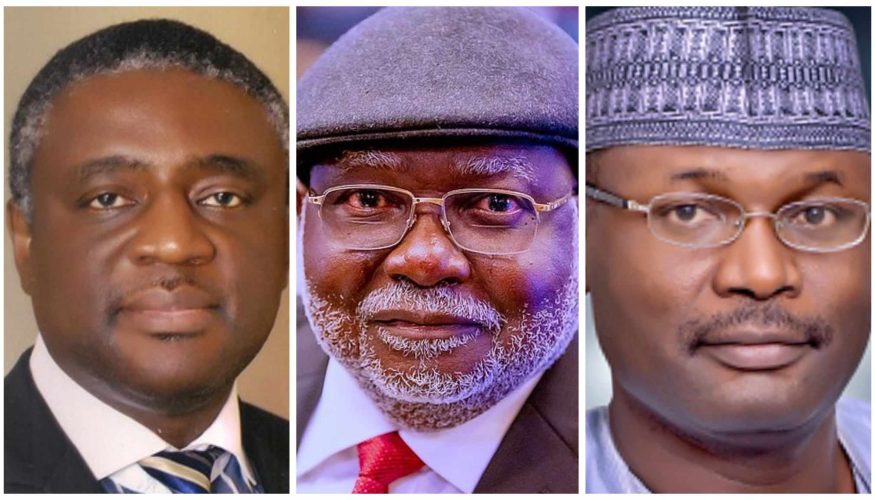

Nigeria’s Judiciary, embroiled in a crisis of public confidence of its own, has once again been called upon to rule on whether the conduct (and outcomes) of the elections were free, fair, transparent and credible, and was up to par with the applicable standards for exercising the democratic franchise. The Judiciary already walks a tight rope, but how it wields its adjudicational powers in the resolution of these high-stake electoral disputes, and the approach it adopts towards that resolution, will shape Nigeria’s fate and stability going forward. The Judiciary must choose now how to navigate the conundrums of either: 1) preserving the status quo and recycling legacies of the blatant abuse of the electoral process; or 2) making a clean, tectonic break from Nigeria’s past and raising the thresholds for what will henceforth be regarded as acceptable, free, fair and transparent elections.

It is our hope that the Judiciary, in spite of its current outlook, will choose to give Nigerians a new hope in the country’s future, new faith in the sanctity of the electoral process and the opportunity to breathe again as a people whose voices and choices on matters of their governance ought to matter.

To join our CITY LAWYER ROUNDTABLE on WhatsApp, click here

To join our Telegram platform, click here

COPYRIGHT 2022 CITY LAWYER. Please send emails to citylawyermag@gmail.com. Join us on Facebook at https://web.facebook.com/City-Lawyer-Magazine-434937936684320 and on TWITTER at https://twitter.com/CityLawyerMag. To ADVERTISE in CITY LAWYER, please email citylawyermag@gmail.com or call 08138380083.

All materials available on this Website are protected by copyright, trade mark and other proprietary and intellectual property laws. You may not use any of our intellectual property rights without our express written consent or attribution to www.citylawyermag.com. However, you are permitted to print or save to your individual PC, tablet or storage extracts from this Website for your own personal non-commercial use.